The Pros And Cons of Modular Nuclear Reactors

Leonard S. Hyman and William I. Tilles

Did you ever get the feeling that you’ve seen this movie before, except with another name? The remake, maybe in color this time or with a younger cast? Well, nothing wrong with recycling but not when you get the uncomfortable notion that the actors don’t know that somebody did it before them. Did you ever get the feeling that you’ve seen this movie before, except with another name? The remake, maybe in color this time or with a younger cast? Well, nothing wrong with recycling but not when you get the uncomfortable notion that the actors don’t know that somebody did it before them.

Take nuclear power. What went wrong last time around? We suggest that a principal culprit was customization. Almost every utility wanted a nuke tailored to its needs, site by site. Thus, each site had its own problems, and solving them produced little experience that helped anywhere else. France, of course, was the main exception. The French state, which owned the utility, settled on one design and repeated it again and again. Of course, the French utility had the scale that U.S. and British's utilities lacked. And the French never shied from dirigisme, state control of the economy. If the government planned to finance, subsidize and insure the industry, it might as well specify what it wanted. Not so in the USA, where we didn’t want the government to tell utilities what to buy, although we had no problem subsidizing and insuring whatever they built.

Today, we applaud the efforts to design nuclear power stations of smaller size, which will achieve economies of scale by constructing identical equipment in a manufacturing setting and shipping the modules to the construction site where they will be assembled. We have yet to establish whether the modular units will be substantially cheaper, and we have a good idea that most of the designs will not solve the nuclear waste problem. We are still determining whether the public will accept the new nukes more warmly than the old ones, too. But we are confident that builders will have less money at risk in any one piece of machinery, which is good.

Here’s our worry. There are at least 21 announced small modular reactor technologies ( as we wrote in a previous report), some with big-name tech backers. It is almost as if some tech entrepreneurs that can no longer find app start-ups to fund have plunged into nuclear energy. Now, let’s do some rough numbers. There are 439 nuclear power plants in the world (92 in the USA, 56 in France, 54 in China and 37 in Russia, 33 in Japan, and 24 in South Korea). Over the coming 20 years, we believe most of these reactors will have to be retired, some in extreme old age. Figure that the new units might average one-tenth to one-quarter the size of the old ones. So maybe a requirement for 4000 units over 20 years. Or 200 units per year. Divide that by 20 different designs. If each producer got an equal share, that would mean ten units per year. We don’t know but have to ask whether that number would yield financing for a factory that could achieve economies of scale. Now add on the nationalism and security issues. Should we expect the USA, France, Russia and China to buy from foreign sources? If they require in-country sourcing, it is more difficult for any manufacturer to achieve real scale. The contestable market for manufacturers might be closer to 100 units per year, maybe less. That might not give room for manufacturing economies of scale.

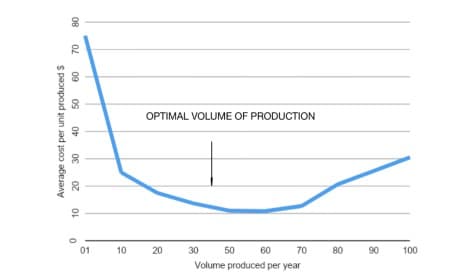

We do not expect to see reliable analyses of the manufacturing costs of SMRs for some time, if ever, because the information would be a competitive secret. We are not even sure that current cost estimates are reliable, as opposed to come-ons to bring in generator companies to sign memoranda of interest, which are not contracts but might convince backers to put up money to build a factory. However, let’s assume that manufacturing a reactor in a factory is not much different than manufacturing an airplane or automobile. Each facility ( or firm) has a U-shaped or saucer shaped cost curve. That is, cost per unit is high when volume is low, hits a low point at a a given volume, and then, eventually rises as the firm hits diseconomies of scale. The cost curve, then, looks like that shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Average cost per unit at given production volumes

Let’s say that the total market per year for the product is 200 units. With the optimal, low-cost-per-unit production point at 50-60 units, the market couldn’t support more than four manufacturers. Whether the nuclear market can support 21 or four manufacturers depends on presently unknown manufacturing cost curves. As good capitalists, you might ask why consumers should care if a bunch of manufacturers put up plants and don’t get enough business to support them and then go under. Well, there are several reasons. For one, we don’t want manufacturers hard up for orders and profits to skimp on the production process. The nuclear plant had better operate safely. Second, owners of nukes will need decades of service. Would they buy plants from manufacturers that look like they might not be around when needed? Third, considering the financial consequences of outages, would they want to take a chance on a cheaper unit or rather pay up for perceived quality? Fourth, and most importantly, would government watchdogs encourage a proliferation of designs, making their jobs harder? We don’t expect many of these SMR providers to get off the ground, especially if the government, the real backer of the industry, decides to opt for uniformity in order to get economies of scale in manufacturing and in regulation. In short, we’d put our money on the big names with long years of servicing their products.

Finally, SMRs, while welcome, neither substantially reduce nuclear costs nor cure the waste disposal problem, although they should reduce the financial burden inherent in big nuclear projects. In other words, they seem like a better way to pursue nuclear energy, which remains the most expensive, environmentally controversial, non-carbon producer. Is there a better way?

By Leonard S. Hyman and William I. Tilles for Oilprice.com

Leonard S. Hyman is an economist and financial analyst specializing in the energy sector. He headed utility equity research at a major brokerage house and has provided advice on industry organization, regulation, privatization, risk management and finance to investment bankers, governments and private firms, including one effort to place nuclear fusion reactors on the moon. He is a Chartered Financial Analyst and author, co-author or editor of six books including America’s Electric Utilities: Past, Present and Future and Energy Risk Management: A Primer for the Utility Industry.

William I. Tilles is a senior industry advisor and speaker on energy and finance. After starting his career at a bond rating agency, he turned to equities and headed utility equity research at two major brokerage houses and then became a portfolio manager investing in long/short global utility equities. For a time he ran the largest long/short utilities equity book in the world. Before going into finance, Mr. Tilles taught political science .

oilprice.com

|