Send this article to a friend:

March

20

2023

Send this article to a friend: March |

We Are in the Eye of the Hurricane – What Happens Next?

On March 14, Bear Stearns, an 85-year-old Wall Street investment bank with a respectable pedigree, announced major liquidity problems. To be clear, “liquidity problems” are bad, but they aren’t the end of the world. “Liquidity problems” is the banking phrase that means, “We’re good for the money, we just don’t have ready cash right now.” That was plausible – after all, Bear Stearns was the 5th largest investment bank in the U.S. They immediately received a 28-day loan from the New York Federal Reserve. But that wasn’t enough – because it turned out they didn’t in fact have “liquidity problems,” they had “solvency problems.” (That’s the banking phrase for, “All the money’s gone.”) Two days later, the Federal Reserve paid JP Morgan $29 billion to acquire Bear Stearns. Now, normally in business, when you acquire a competitor, you pay for it – but JP Morgan executives took one look at the toxic hellscape of Bear Stearns’ balance sheet and would’ve fled the boardroom screaming, except the Fed’s agents had locked the door. Just for a moment, try to imagine for a moment a deal so incredibly bad you have to get paid $29 billion to say yes. A year before this shotgun wedding, Bear Stearns was worth $25 billion. By the time the deal was signed, its stock had lost 97% of its value and the bank was presumably worth about -$29 billion. At the time, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke defended the move by citing contagion fears:

In other words, his logic was, “We did this now to prevent bigger problems later.” Jamie Dimon, head of JP Morgan, agreed:

Mission accomplished? Nope. Not even close. In hindsight, Bear Stearns’ stunning fall from grace wasn’t the end of the financial crisis, but the beginning. “How do you go bankrupt? Two ways: Gradually, then suddenly” I think about this Hemingway quote a lot. It seems especially appropriate when looking back on the Great Financial Crisis. As I remembered it, as I lived it, the bad news came all at once: Bear Stearns collapsed. Then Lehman Brothers, IndyMac, Countrywide, the government nationalized Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac – and suddenly the Federal Reserve was bailing out every bank in the world, hundreds of billions of dollars gushing out of the central bank like water from a broken fire hydrant. It feels like the global financial system fell apart during one nightmarish three-day weekend. But memory’s a funny thing. Because that’s not how it happened. There were no sudden crises, no earth-shattering events for the next six months. Until September, 2008. That’s when the federal government nationalized the two lending insurers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. One week later, Lehman Brothers, the 150-year-old global investment bank and one of the most respected firms on Wall Street, filed for bankruptcy. The next day, the Federal Reserve bailed out AIG, the largest insurer in the U.S. Before the end of the month, Washington Mutual was seized by the FDIC. Wachovia, another major U.S. bank had a shotgun marriage to Wells Fargo. And the two largest investment banks, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, shapeshifted into “bank holding companies” so they could line up with the rest at the Fed’s bailout window. Here’s my point: The last financial crisis started slowly – and grew suddenly. If we look at even a primitive timeline of key events in the 2008 financial crisis, my point becomes clear:

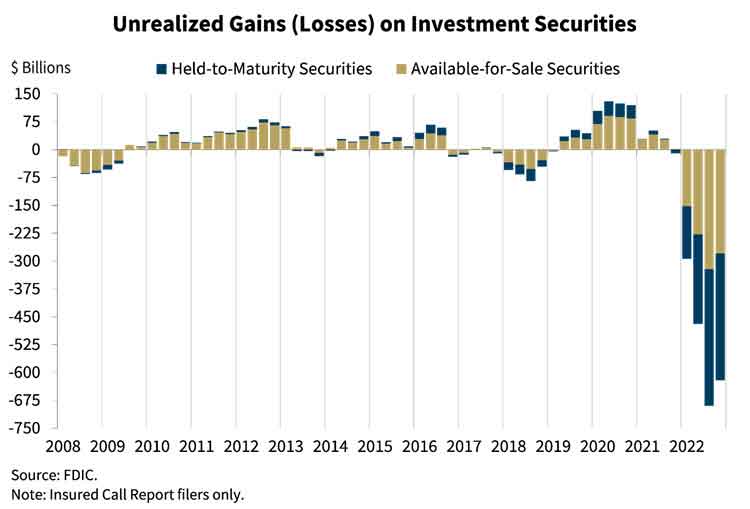

Will this time be different? Probably not. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if we saw a months-long quiet period after the Silvergate and Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank failures. I’m calling this the eye of the hurricane. Here’s the thing: every bank is facing the same issues that toppled SVB. Take a look at what Patrick McKenzie called “one of the most important charts in the financial world,” courtesy of the FDIC:  via FDIC The U.S. banking system has lost $620 billion (so far). The losses will continue, because they’re due to the Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes. I plan to discuss this in further detail tomorrow. So what’s the lesson here?

(For example, today at 2 a.m. Credit Suisse was rescued by a $54 billion line of credit from the Swiss National Bank. That’s the first central bank bailout since 2008.) I believe we’re in the eye of the hurricane at the moment. Here’s my concern. When things calm down, it’s easy to forget that the hurricane ever happened. But the hurricane hasn’t disappeared – far from it.

|

Send this article to a friend:

|

|

|