Send this article to a friend:

November

12

2024

Send this article to a friend: November |

Europe Is Finalizing Preparations for a Gold Standard

To prepare for a monetary system based on gold, they are buying gold to equalize their reserves to the eurozone average. This balancing of gold reserves in Europe is a key topic I have written about extensively. And now, additional evidence of these plans has come out, this time from Konrad Raczkowski, former Minister of Finance of Poland. Raczkowski recently argued official gold reserves in Europe must be evenly distributed relative to GDP, which “in the near future … will be the new gold standard.” His statement adds to a vast body of proof regarding Europe’s preparations for a gold standard.

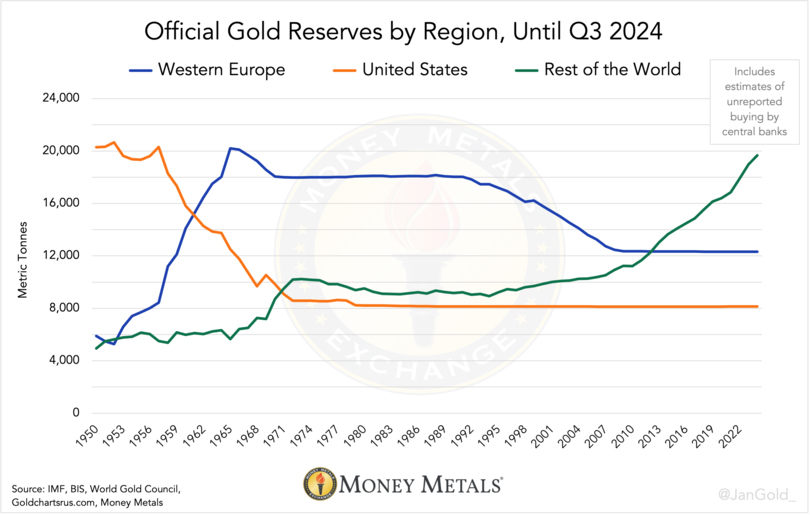

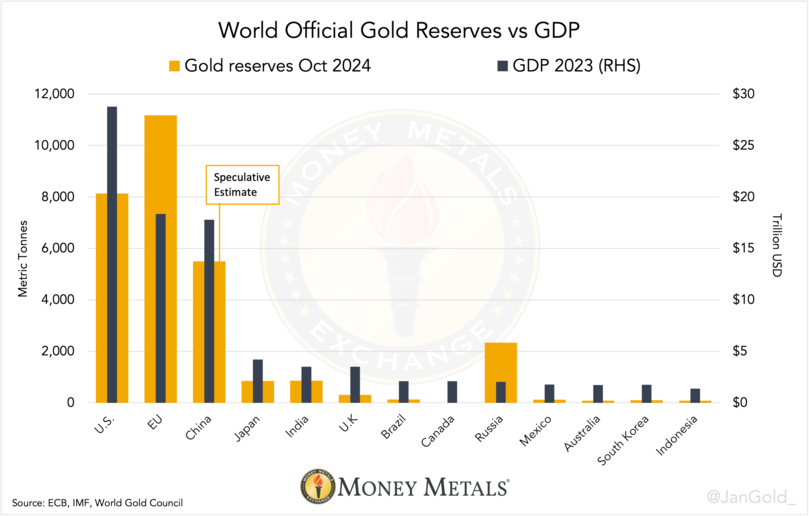

As the United States, issuer of the world reserve currency, has arrived at a critical phase in its debt spiral and as geopolitical tensions keep mounting, it’s of paramount importance we evaluate what gold’s role will be in the international monetary system moving forward. Gold Is Central Banks’ Plan B Most of the largest central banks have a “Plan B” when their paper policy goes haywire, and this backup plan is, to a certain extent, coordinated between them. The first seeds of Plan B were planted by European central bankers and politicians in the 1970s. Only the U.S., together with some of its most obedient vassal states, has been unwilling to cooperate. Plan B, of course, is gold, owned by virtually every monetary authority on this planet and bought by non-Western central banks in record amounts in the past years in response to dollar weaponization and debasement (see chart 1 below). A marked change in the international monetary order awaits us. Why European Nations Want to Evenly Spread Gold Reserves During the demise of Bretton Woods, it was clear that several European countries wanted to switch to a gold standard. They couldn’t pull it off at the time, partly because the United States was using its military strength to block such efforts. Another reason was that the world’s monetary gold was unevenly distributed at the time. Most metallic reserves were held in Western Europe1.

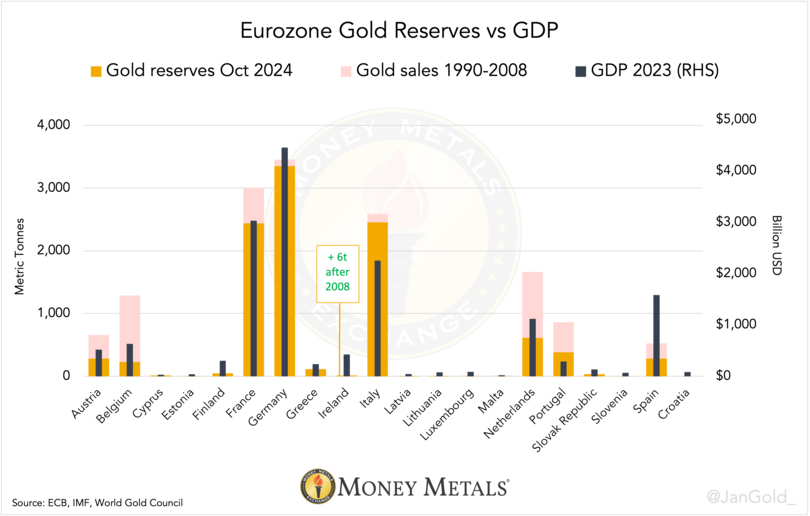

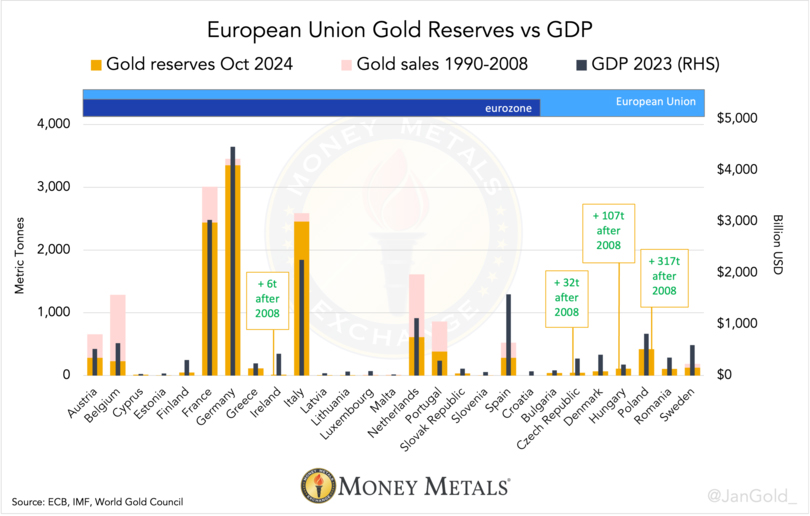

Chart 1. Official gold reserves are more dispersed across the world than ever. When the world switches to a new monetary system, that new system will thrive best if all countries have an equal amount (proportionally) of the new monetary unit. In the 19th century, as most countries went on the classic gold standard, gold demand increased, which pushed up the price of gold and led to deflation (gold was the unit of account). The more skewed the current distribution of official gold reserves, the less smooth a transition towards an international monetary system based on gold. In the early 1990s, European central banks began selling gold reserves. The central bank of the Netherlands (DNB), for example, sold 400 tonnes in 1992. The gold was sold through the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), off the market, to the Chinese central bank (PBoC). This was the first step towards a more balanced distribution of gold. As selling by Europe went on, the gold market got worried that uncoordinated sales were destabilizing the market and driving the price down. As a result, in 1999, at the annual IMF meeting in Washington DC, fifteen European central banks signed an agreement to coordinate their sales2. This agreement would become known as the Central Bank Gold Agreements (CBGA). In the CBGA, they stated that “gold will remain an important element of global monetary reserves. The collective sales will be limited to 2,000 tonnes over the next five years, about 400 tonnes per year.” The signatories also announced that their lending would not increase over the same five-year period (they had 2,119 tonnes on lease in 1999). The announcements prompted an upward reversal in the gold price—much of the uncertainty surrounding the scale of gold selling by the official sector had been removed. CBGA was repeatedly extended, up until 2014, although most of the selling stopped after 2008. CBGA seemed like an agreement for coordinated gold sales. But for those paying close attention, it was obviously meant to equalize gold reserves among countries relative to GDP. Only medium-sized economies in Europe sold heavily, while large economies sold very little. Additionally, of the small countries, Cyprus, Estonia, and Lithuania, didn’t sell an ounce of gold during the “concerted programme of sales.” And Ireland even added half a tonne in 2007 and continued buying after 2008.

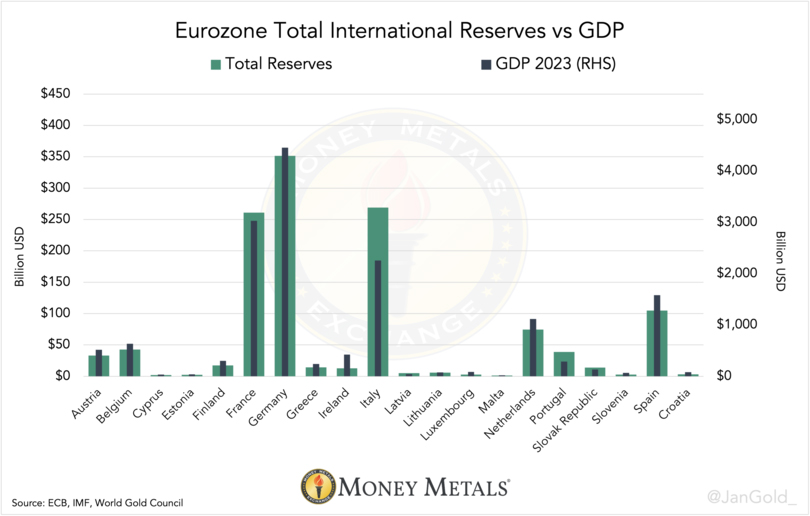

Chart 2. Eurozone Gold Reserves vs GDP. Source: ECB, IMF, World Gold Council, Money Metals Exchange. Spain is an outlier in chart 2, although it has more foreign exchange than the other countries. Total reserves (gold and foreign exchange) in the eurozone are more accurately spread than just gold.

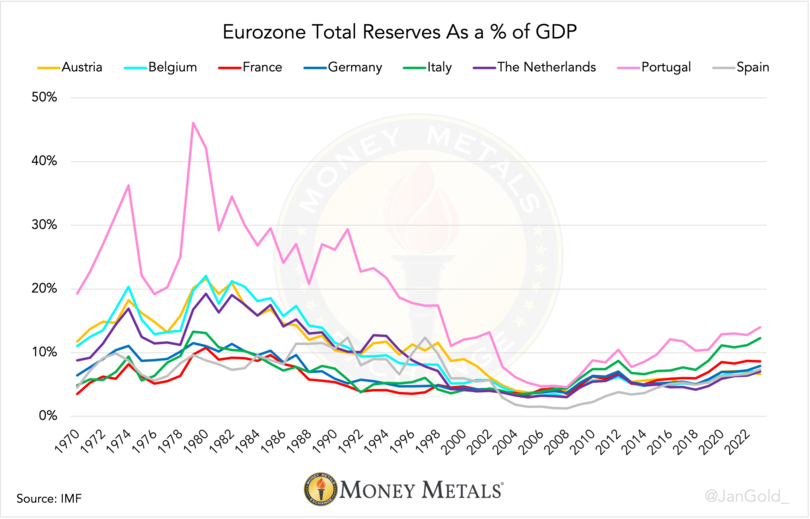

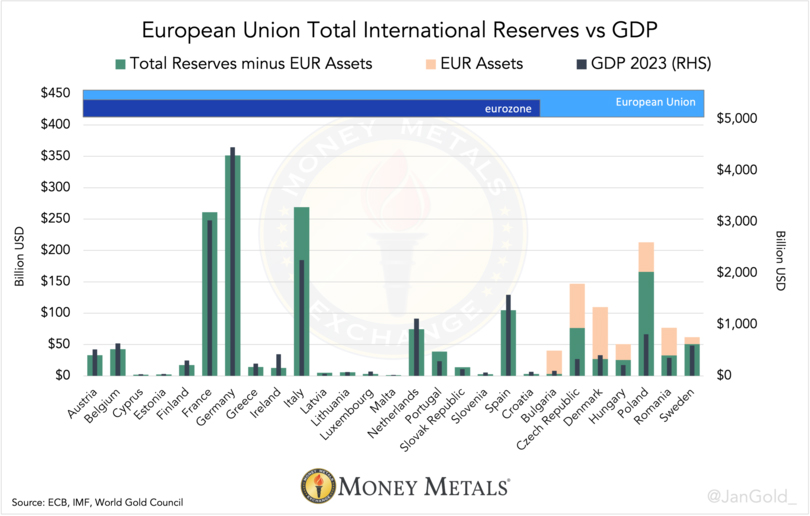

Chart 3. Eurozone Total International Reserves vs GDP. Source: ECB, IMF, World Gold Council, Money Metals Exchange. Within the eurozone, some central banks (that hold too little or too much gold on a relative basis) might cooperate by swapping foreign exchange for gold before gold is revalued. That way, they enjoy the same advantages in their gold revaluation accounts, which can be used to offset bad debt on their balance sheets. This would be the crown on the monetary reset. When one sees a visual representation of the total-reserves-to-GDP ratios within the eurozone over time, the coordination of reserves management among these countries is astounding.

Chart 4. Eurozone Total Reserves As a percent (%) of GDP. Source: IMF, Money Metals Exchange. Remarkably, when I asked central banks about harmonizing reserves within the eurozone, they all replied there is no such policy! Countless Freedom of Information (FOI) requests submitted throughout Europe, directed at central banks and Ministries of Finance, all yielded nil. Sometimes, for example, in the case of Belgium, I was told the subject was confidential and gold management documents couldn’t be disclosed on grounds of “a legal obligation of secrecy” laid down in a law for its central bank from 1998 (just before CBGA was launched). After a long trajectory of discussing my FOI requests with civil servants in the Netherlands and waiting for months to get a response, they ultimately refused to send me any document related to international cooperation on gold policies. Europe’s Open Secret Gold Balancing Act Although equalizing gold reserves in Europe is (somehow) not official policy, I have found numerous statements from central banks that prove their ongoing balancing efforts. In the annual report 1992, DNB comments on the sale of 400 tonnes:

DNB sold another 650 tonnes from 1992 until 2008. After the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008, the Minister of Finance of the Netherlands, Jan Kees de Jager, was asked in parliament for the main reason why the Dutch central bank had sold more than 1,000 tonnes of gold since 1992. His answer:

When he was asked who the buyers were, he answered:

Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad covered the 400 tonnes sale by DNB to the PBoC in 1992 and mentioned:

Even China was in on balancing reserves. We can read a similar perspective from the Swiss central bank—which was part of CBGA but is not part of the European Union—on why it sold 1,300 tonnes of gold:

A statement from the central bank of Austria (OeNB) addresses its gold to total reserves and GDP ratio:

OeNB reveals that gold and foreign exchange reserves are balanced relative to each other and the size of the Austrian economy, affirming the correlations shown in charts 2, 3, and 4.

OeNB officials showing Austrian monetary gold after 90 tonnes from London were repatriated in 2018. Left, OeNB Director Kurt Pribi, right, Governor Ewald Nowotny. In 2023, it was disclosed on the website of the central bank of France:

Because the gold price and France’s GDP are not static, the Banque de France’s citing of a gold-to-GDP ratio of 4% must be viewed in comparison to its peers. Ostensibly, as Germany, France, and Italy hardly sold any gold since the 1990s, many other “important gold-holding nations” aimed to get on par with them by either selling or buying gold. No country’s GDP grows steadily relative to other economies, so gold-to-GDP ratios can somewhat differ but are remarkably proportionate (chart 2).

Eastern Europe Implements Gold PlanBy design, all countries in the European Union but not in the eurozone will someday adopt the euro. Regarding gold reserves, central banks in Eastern Europe historically held less yellow metal than in Western Europe. And so in 2018, the largest economies in Eastern Europe began purchasing gold to catch up. Since 2018, Poland has bought 317 tonnes (+208%), Hungary added 107 tonnes (+3376%), and the Czech Republic increased its holdings by 32 tonnes (+141%).

Chart 5. For “advanced economies” such as Denmark and Sweden, it’s politically sensitive to buy gold. European Union (EU) Gold Reserves vs GDP. Source: ECB, IMF, World Gold Council, Money Metals Exchange.

Chart 6. European Union Total International Reserves vs GDP. Source: ECB, IMF, World Gold Council, Money Metals Exchange. After subtracting euro assets from foreign exchange held by central banks in the EU but outside the eurozone, only Poland and the Czech Republic have too much reserves in total. Bulgaria, Denmark, Hungary (my estimate), Romania, and Sweden’s total reserves to GDP ratios are exactly matched to that in the eurozone. These are amazing statistics, considering these policies officially don’t exist, according to central banks!

Hungarian monetary gold held domestically displayed for the central bank’s 100th anniversary in 2024. Hungary has bought and repatriated gold since 2018. The Czech Republic announced it will keep buying gold until it reaches 100 tonnes, and Poland says it is aiming for a little less than 600 tonnes. Both levels would get these countries more in line with the eurozone average gold-to-GDP ratio. Although I had my suspicions, up until recently, I had never read anything from Eastern Europe about balancing gold to GDP ratios. But then I saw a podcast by Parallel Systems from October 16, 2024, that discussed a quote from Konrad Raczkowski, former Minister of Finance of Poland. The quote was taken from a recent article by Raczkowski in a print magazine published by the central bank of Poland (NBP). From Raczkowski:

As time goes on, this story about balancing gold reserves for a coming gold standard keeps strengthening. Note, Raczkowski mentions the same gold to GDP ratio as the Banque de France, which is based on data from 2023. Because the gold price has significantly increased this year, the average ratio would be higher by now. More context about Raczkowski’s remarks was provided by Aerdt Houben, Director of Financial Markets for DNB, in an interview conducted by Anna Dijkman from Het Financieele Dagblad in 2023. (Because Dutch is my native language, that’s where I find the most evidence.) According to Houben, equalizing gold reserves was a political decision taken in the 1990s. In a crisis, the gold price “shoots up,” and gold will be the foundation of a new monetary system. From the interview:

You can imagine these quotes made me fire FOI requests all over Europe because they revealed there had to be a political consensus for equalizing gold reserves. Alas, to no avail. The European gold plan is probably “unofficial” not to upset Uncle Sam. Europe’s Path Towards a New Gold Standard Next to equalizing metallic reserves, Europe stikes a positive note when communicating about gold, several countries have increased security of their reserves by repatriating their gold, and some even disclosed to have upgraded their bars to current wholesale industry standards, so the world can be confident their gold is ready to be deployed in international markets when needed. No central bank is served by sudden shocks in the financial system. If the gold price would rise too rapidly, a panic might ensue. After 2008, European central banks have changed how they communicate about gold. On central bank websites, we can read about the unique properties of this financial asset. These central banks want to convey to the public the inherent risks of paper money that gold is immune to and have the price of gold rise gradually. For example, this appears on the website for the central bank of Italy:

Exceptional words from an institution that itself issues a paper currency and can go belly up. We can’t conclude Banca d'Italia trusts its own currency, can we? The Dutch central bank stated on its website:

The French central banks suggests that gold is “the ultimate store of value.” According to former President of the German central bank, Jens Weidmann, gold is “the bedrock of stability for the international monetary system.” And a member of the Board of the Bank of Finland called gold “a genuinely global means of payment [and] a safe haven against both economic and political risks.” More to the East, the Hungarian central bank discloses it bought gold because “it may play a stabilizing role … in times of structural changes in the international financial system.” The President of NBP, Adam Glapiński, points out that “gold is free from credit risk and cannot be devalued by any country’s economic policy.” All these central banks are pro-gold.

Adam Glapiński presenting NBP’s gold reserves after repatriating in 2019.

In 2017, Bundesbank Executive Board member Carl-Ludwig Thiele showed the press part of Germany’s gold reserves after repatriation operations from New York and Paris were completed three years ahead of schedule3. Next to a pro-gold communication policy, several European central banks have repatriated gold, mostly from New York and London. Up till now, Germany, the Netherlands, France, Austria, Poland, Hungary, and Serbia have brought gold to domestic vaults considering cost efficiency, security, and liquidity objectives. That we know of France, Germany, Sweden, and Poland made all their gold bars adhere to “LBMA Good Delivery” standards for easy access to the global OTC market. Consequently, their metal is liquid and ready for international settlement. From the Banque de France:

In comparison, the vast majority of the U.S. monetary gold does not comply with current wholesale industry standards and is not liquid. A Global Gold Standard Any currency works optimally if all market participants own it and are willing to buy and sell it. Same goes for gold, Europe’s plan B. This is why Europe has an incentive to encourage central banks and people around the world to own gold. The better gold is distributed around the world, the more liquid gold is, and the more suited it will be as a foundation for a new monetary system when the paper game comes to an end. As we have discussed, in the 1990s, Europe started selling gold for developing economies to level up. China and other developing countries were probably aware of the distribution of gold by then. The website of the Bank of China—a state-owned bank—states:

Because GDP tends to be correlated to the broad money supply (M2), a future gold standard will likely be a system of gold price targeting by central banks rather than the classical gold standard. On a classical gold standard, people can redeem national currency for gold at the central bank. With gold price targeting, people can exchange national currency for gold in the free market, in which the central banks aim to stabilize the gold price. If a country has a balance-of-payments deficit, it can devalue against gold. After all, national currency devaluations are a fact of life. Gold will be the reality check of the international monetary system. The distribution of gold will never be perfect, though the fact thousands and thousands of tonnes (chart 1) have been bought by countries in the East since 2008 has been encouraging for those who believe “Plan A” will inevitably come to an end.

Chart 7. World Official gold reserves versus GDP. Source: World Gold Council, World Bank, Money Metals Exchange. As wars rage on and government debt levels keep rising, there will come a point of inflection. Given the pace at which central banks keep buying gold since the war in Ukraine, we may conclude they foresee the end of the dollar hegemony is nearing. Notes:

Previous Articles on this Subject:

|

Send this article to a friend:

|

|

|