As the US Treasury Runs Out of Creditors, Its Options Dwindle

Jonathan Newman

Are the chickens coming home to roost for the US Treasury? As Ryan McMaken noted in a recent Mises Wire article, the United States is in a debt spiral and there’s no easy way out. Are the chickens coming home to roost for the US Treasury? As Ryan McMaken noted in a recent Mises Wire article, the United States is in a debt spiral and there’s no easy way out.

The problem is multifaceted, but the origin is profligate government spending. While it typically spikes during crises, spending is increasing at an alarming rate even outside of crisis periods. And tax revenues are not keeping up, which means ever-deepening deficits. Government expenditures spiked during the 2020 crisis, but even ignoring those spikes, annual spending has increased by about $1.6 trillion since 2019, while tax receipts have only increased by about $600 billion.

The government must borrow to make up the difference, which has led to a mountain of debt. Total public debt has ballooned to over $32 trillion, which is over 180 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), excluding government spending and transfers.

Due to the unpopularity of price inflation and the inexorable tendency for the market to reestablish interest rates that accord with people’s real time preferences, the Fed has allowed interest rates to rise. This, combined with the sheer size of the debt has caused the government’s interest payments to increase to unprecedented heights. In 2020, interest payments were a little over $500 billion, but they have almost doubled since then.

Congressional Budget Office projections show that these interest payments will take up ever-larger portions of the federal budget, causing deficits to sink even further. The government will have to use more debt to pay off past debts.

Figure 1: Congressional Budget Office: Deficits as a percentage of GDP

On top of all of this, the US Treasury is running out of buyers for its debt. The Fed, which has always been a ready buyer of government debt with newly created money, is allowing its holdings of US Treasury securities to roll off its balance sheet. It cannot resume monetizing the debt without exacerbating price inflation, which is still above its stated target of 2 percent.

Figure 2: Treasury securities held by the Federal Reserve

Source: “Assets: Securities Held Outright: U.S. Treasury Securities: All: Wednesday Level,” FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, last updated November 22, 2023. Data from Factors Affecting Reserve Balances, Federal Reserve Statistical Release H.4.1 (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve).

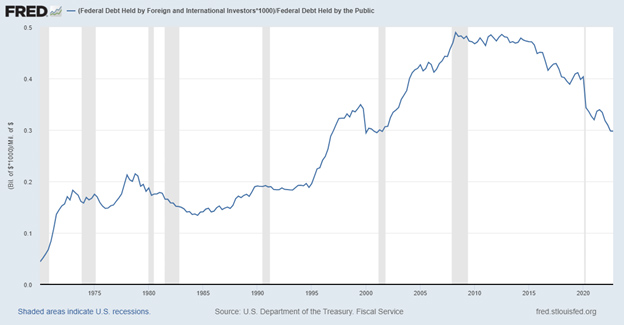

Like the Fed, foreign governments such as China and Japan are also reducing their purchases of Treasurys, leaving the US with a smaller customer base for its debt. As Robert P. Murphy showed in a recent talk, the proportion of debt held by foreigners has been declining since 2014.

Figure 3: Federal debt held by foreign investors as a proportion of federal debt held by the public

This too-much-supply and not-enough-demand phenomenon came to a head at an October Treasury auction that turned into a fiasco when thirty-year yields reached 4.837 percent and primary dealers, who are required to purchase any leftovers, had to mop up over 18 percent of the auctioned debt.

So, everybody’s appetite for US government debt is running low, and that includes foreigners, the government’s own money printer, and favored financial institutions.

What does this mean for next year, when $7.6 trillion in government debt will mature? This is almost a third of all of the US’s outstanding debt, which means a ton of supply is about to hit this market with already declining demand. Unless the government decides to tighten its belt and dramatically reduce spending (flying pigs are more likely), it will have to replace maturing debt with more new debt.

Here are some possible scenarios:

- A financial crisis and official recession occur, which gives the Fed “permission” to flood the economy with new money, lower interest rates, and make another massive purchase of government debt, as it has in prior crises. The issue with this scenario is that the Fed is still in the throes of its battle against price inflation. Although some economists say that recent official price inflation statistics show that the Fed is done with its rate hikes, measures of market inflation expectations have remained elevated in the past few months. We could be heading into a 1970s-style stagflation, in which the Fed must choose (according to the conventional Phillips curve framework) between dealing with unpopular inflation and unpopular unemployment. If we are capable of learning from experience, we know what it takes to get out of such a mess: a painful but healthy and necessary correction precipitated by a Volcker-style sharp increase in interest rates.

- Treasury auctions continue to founder, leading to a debt crisis. Treasury yields skyrocket as the whole world loses confidence in the US government’s ability to repay its debts. It’s difficult to imagine such a globally catastrophic scenario, especially since the US has its own money printer (see scenario 1). It seems the Fed and the US government would happily choose to inflate as much as necessary to avoid such an outcome.

- The US government performs a “soft default,” similar to its actions in the 1930s and in 1971, in which the dollar is transformed in such a way as to rescue the government from its debt obligations. In the 1930s, the government devalued the dollar by changing its gold redemption ratio from $20.67 to $35.00 per ounce, as well as limiting and prohibiting gold ownership for US citizens. In 1971, Nixon “temporarily” (read: permanently) reneged on the US’s promise to redeem foreign governments’ dollars for gold. One avenue the US could take along these lines is the implementation of a central bank digital currency(CBDC). A CBDC could be programmed to have negative interest rates and other incentives that would push CBDC holders to buy government debt. Such a tyrannical move would be disastrous for citizens, but the ability to control interest rates, increase tax revenues, and direct and stimulate spending makes this option very attractive to a debt-riddled government that has painted itself into a corner.

Of course, we could see a combination of these unfold in 2024 and beyond. As I stressed in a recent talk, there is a lot of uncertainty surrounding what the Fed will do. We’ve seen the Fed do many unprecedented things in just the past two decades. The Fed is used to stretching its own power and scope in ways that nobody fully realized the Fed could or would.

Some things are certain, however. Reckless fiscal and monetary policy have put the US government and the economy in this mess, and the Fed and the government will use reckless fiscal and monetary policy to try to escape it.

Dr. Jonathan Newman is a Fellow at the Mises Institute. He earned his PhD at Auburn University while a Research Fellow at the Mises Institute. He was the recipient of the 2021 Gary G. Schlarbaum Award to a Promising Young Scholar for Excellence in Research and Teaching. Previously, he was Associate Professor of Economics and Finance at Bryan College. He has published in the Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics and in volumes edited by Matthew McCaffrey and Per Bylund. His research focuses on Austrian economics, inflation and business cycles, and the history of economic thought. He has taught courses on Macroeconomics and Quantitative Economics: Uses and Limitations in the Mises Graduate School. He is the author of two children's books: The Broken Window and Ludwig the Builder. His commentary appears regularly in the Mises Wire and Power & Market.

www.butlerresearch.com

|

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/images/live/s_gold.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/images/live/s_silv.gif)