Send this article to a friend:

September

26

2024

Send this article to a friend: September |

Back to Basics

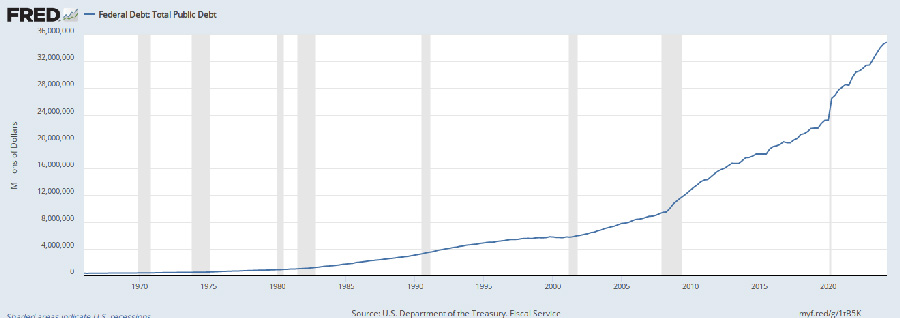

Financial markets are exercises in crowd psychology. Analysts make good money analyzing the latest market moves and predicting the next ones. Today’s analyses often contradicts yesterday’s and yesterday’s errant predictions stops no one from making predictions today. It would be trivially easy to keep score, but few do; it would endanger six- and seven-figure compensation packages. What most everyone wants to obscure is the essence of the game: guessing where the crowd is going next. Greatly aiding this obscurant project is the rubberiness of one of the measuring sticks: the value of fiat currencies. If you’re keeping score in dollars, the Dow Jones Industrial Average is up over 3.5 times from its 1999 high. If you’re keeping score in real money—gold—the Dow topped a quarter of a century ago at just over 42 (Dow divided by the dollar price of an ounce of gold) and is down over 60 percent since (it’s now 16 and change). Everybody has a choice of measuring stick: either a precious metal that has served as money for centuries and has consistently preserved its value against real goods and services, or fiat currencies that historically have never preserved their value and are backed only by promises, always broken, not to create too many of them. The stock-selling industry chooses the latter. Measured by gold, the stock market has been in a quarter-century bear market. Crowd psychology suggests that even measured by elastic fiat currencies, it will soon be in a deep and lengthy bear market. Continuous fiat currency inflation and suppressed interest rates have fed an equity mania since Alan Greenspan flooded the financial system with central bank fiat credit after the 1987 stock market crash. That maneuver has been repeated so often that it’s known as the “Fed Put.” A put option gives its holder a right to sell an asset at a particular price, so the Fed Put refers to the central bank pegging asset prices. BTFD is the well-known acronym for “Buy the F**king Dip,” and that strategy has rewarded the fearless time and again. “No fear” aptly characterizes the equity crowd’s psychology. That legendary investor Warren Buffett is selling and his company, Berkshire Hathaway, has record cash reserves is ignored, as are stretched valuations and other indicators that might disturb consensus belief that over anything but the very short term, stock prices only go one direction. Artificial Intelligence is the current speculative hook, just as dot-com was before a vicious bear market kicked off the new century. Although some “transformative technology” companies thrive, the fervid hopes generally far outrun actual performance, even for technologies such as the Internet that have had an enormous impact. A bear market in bonds began in the summer of 2020. Yields on U.S. Treasury 10-year notes bottomed, which means prices topped. Since then, yields have clearly broken downtrend lines (prices have broken uptrend lines) stretching back to 1981. The new yield uptrend roughly corresponds to the inflection in the quantity of U.S. government debt. Inflection, when a gentle rise suddenly becomes a steep one, is the inevitable acceleration point of exponential functions, which U.S. debt most certainly is.

Interest rates will trend upward with the exploding quantity of debt, and the ascent could be correspondingly steep. The rising fiat currency price of gold is clearly registering debt debasement. Rising interest rates produce a vicious feedback loop for the U.S. Treasury. They raise debt service costs, which require the Treasury to borrow more. Interest expense is now the third largest item in the federal budget and is running at an annualized rate of over $1 trillion per year. Creditors add to this pressure on the bond market. As they lose money on their existing holdings and bear market psychology takes hold, they sell to limit their losses, exacerbating the downtrend. The yields on corporate, agency, municipal, and individual debt rise with government-debt yields. Rising interest rates reduce the discounted future value of assets, including equities and real estate, thus reducing asset prices. As creditworthiness deteriorates and insolvency and bankruptcies increase, the overall quantity of debt will finally start to shrink. Debt is the foundation of the global economy and the medium of exchange. Because it is the medium of exchange, debt contraction—from the write-offs of worthless debt and the unwillingness of a shrinking pool of solvent creditors to extend credit—is inherently deflationary. The bear market in bonds will reach its own inflection point, with prices plummeting and yields soaring. Those who place their faith in central banks and speculate accordingly will be crushed. Central banks don’t control interest rates; markets do. There is a well-paid cottage industry that tries to predict central banks’ every move, but the best “seer” is market-determined short-term interest rates. The Federal Open Market Committee follows rather than sets market rates. Its recent fifty-basis-point reduction in the federal funds rate target simply confirms the market trend. The three-month treasury-bill rate has been falling since June, and has fallen by about fifty basis points. Following market rates, the Fed repeatedly lowered its federal funds rate target and discount rate in the 2007-2009 financial crisis. It didn’t prevent that crisis and did nothing to stop the enormous destruction wrought by derivatives. The notional value of derivatives has only grown since then and estimates of the total size of that market range from $1 to $3 quadrillion (a thousand trillions), or roughly 9 to 27 times global GDP. Derivative dealers supposedly offset the risk of their derivative books with matching positions—for every buy there is a corresponding sell. However, the dealer derivative market is so concentrated among a handful of large banks that it would take the failure of only one to turn matching positions into open exposures and bring the entire market crashing down. This is essentially what happened when Lehman Brothers went bankrupt in 2008. Global central bank assets are in the neighborhood of $40 trillion, or 1/25 to 1/75 of the derivatives market. When derivatives collapse, central banks will extend massive amounts of their fiat credit, but they’ll be fighting a forest fire with squirt guns. There was no such debt and derivatives overhang during the Great Depression, consequently, the coming economic collapse will dwarf that tragedy. The tax base will shrink, interests rates will be well into double digits, inflating fiat currencies will be overwhelmed by debt deflation, and governments, as always, will produce nothing. The bottom line: most of them will be flat broke, unable to do the things our current rulers and their citizens think they ought to be doing. Western governments will be unable to fund either their welfare or warfare states (there is a substantial welfare state component in the warfare state). That won’t go down well with dependent populations, and civil unrest is a virtual certainty. Governments will be contending with unorganized chaos—riots and the like—and probably organized insurrection and secession efforts as well. Of course, governments will resort to centralized totalitarianism, but surveillance, apprehension, incarceration, concentration camps, and mass executions cost money and require personnel to administer. The police and military (assuming martial law) will shun payments in depreciating government scrip. Many of them will decide that either criminality or offering “protection” from criminality pays better as warlord culture takes hold. We’re already getting a taste of that in the de facto power domestic and immigrant gangs exercise in some cities and towns. Government and its mainstream media hasn’t wholly suppressed the truth about that emergent phenomenon, which is going to get much worse. Many modern absurdities will be discarded, and old verities will be rediscovered. Severe economic contraction is a cold slap across the collective face. When mass poverty sets in and all hell breaks loose, gender and pronoun choice will be seen as the bizarre affectations they are. Among the hordes of unemployed, the dyed, tattooed, and pierced may come to regret those alterations to their appearance. Businesses will be choosy. Coveted jobs will go to those who can best perform them, not to those who tick the most DEI boxes. Business will insist on the cheapest and most reliable energy, which will usually not be renewables. People will have more pressing concerns than whether or not the climate is changing, like whether or not they can survive. A degree or two warmer will cut down on the heating bills. Economic collapse will assuredly write the final chapters in The Decline and Fall of the American Empire. Government always fail; the only ones that haven’t are those that are in the process. The financial and economic crash will push many already-tottering governments off the cliff. What emerges will be different geographic boundaries and governments than what we have now. Existing nations will splinter into smaller units, and today’s centralized, parasitic dinosaurs will be a thing of the past, driven to extinction by the unstoppable forces of decentralization, bankruptcy, and their inability to produce. It will be a hard landing for the economically net-negative, particularly the Overclass that has profited so mightily from current arrangements. The realization will dawn that the economically net-positive—the productive—are the most valuable asset. They will migrate to those jurisdictions where they are treated the best—minimal taxes and regulations, strong protection of contract and property rights, sound money, and maximum freedom to produce and trade. Competence, innovation, thrift, and investment will be prized, and among the more enlightened of those political systems that emerge from the chaos, there will be intense competition to attract the productive. This may seem like a pipe dream, but how else will decimated societies with failed governments rebuild? It will be back to basics. The basics of sound economic growth and progress have always been simple to enumerate but difficult to achieve. They require relatively small, constrained governments, which require effective restraints on the cupidity and power-lust of those who run them. Perhaps there will be a backlash of revulsion and recrimination at the morally obscene and thoroughly discredited notion of dumping debt on future generations. There should be. Small, constrained government is affordable government, and affordable will be the key characteristic of those that emerge. To have any chance of long-term survival, governments and rulers will have to be relegated to a role subordinate to protecting rights and liberties (nothing America’s founding fathers didn’t know). They will find that distasteful, but it will give the true drivers of economic and social progress—the productive—their chance to rebuild and flourish. In the recent presidential debate, neither the candidates nor the moderators mentioned the national debt. Instead, both candidates pledged not to cut current programs and to institute new programs and tax breaks that will increase it. They both pledged fealty to the warfare and welfare states and maintenance of the empire. They are seemingly oblivious to the looming disaster set to destroy either of their presidencies. So, “no fear” characterizes the bond market as well as the equity market. Crowd psychology is virtually unanimous and invariably wrong at big turning points. We’re at such a turning point. There is money to be made lending money to the U.S. government short term, for a period no longer than six months, what’s known as a T-bill roll. The government won’t technically default; it can always redeem its fiat debt with more fiat debt. Short-term rates will ratchet higher with the rest of the yield curve. By rolling your investment, you can be a beneficiary rather than a victim of higher rates. Any other exposure to debt or equity markets is playing on the beach just before the tsunami makes landfall.

Robert is a writer, investor, attorney, and former bond trader. His website is straightlinelogic, and his most recent novel is The Golden Pinnacle, available on Amazon, Kindle, and Nook. He is also a regular columnist for thesavvystreet.com. |

Send this article to a friend:

|

|

|