Credit Crunch: The Money Supply Has Shrunk For Eight Months In A Row

Ryan McMaken

Money supply growth fell again in June, remaining deep in negative territory after turning negative in November 2022 for the first time in twenty-eight years. June's drop continues a steep downward trend from the unprecedented highs experienced during much of the past two years. Money supply growth fell again in June, remaining deep in negative territory after turning negative in November 2022 for the first time in twenty-eight years. June's drop continues a steep downward trend from the unprecedented highs experienced during much of the past two years.

Since April 2021, money supply growth has slowed quickly, and since November, we've been seeing the money supply repeatedly contract—year-over-year— for six months in a row. The last time the year-over-year (YOY) change in the money supply slipped into negative territory was in November 1994. At that time, negative growth continued for fifteen months, finally turning positive again in January 1996.

Money-supply growth has now been negative for eight months. During June 2023, the downturn continued as YOY growth in the money supply was at –12.4 percent. That's up slightly from May's rate of –13.1 percent, and was far below June's 2022's rate of 5.7 percent. With negative growth now falling near or below –10 percent for the third month in a row, money-supply contraction is the largest we've seen since the Great Depression. Prior to March through June of this year, at no other point for at least sixty years has the money supply fallen by more than 6 percent (YoY) in any month.

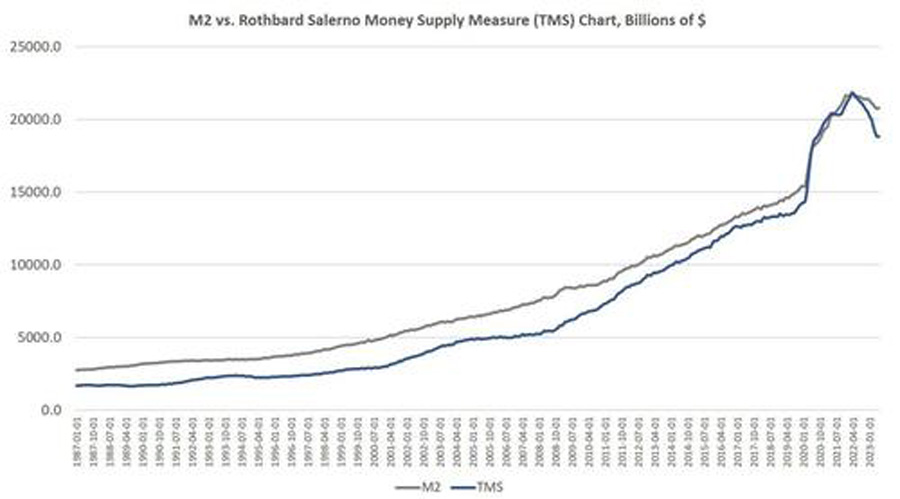

The money supply metric used here—the "true," or Rothbard-Salerno, money supply measure (TMS)—is the metric developed by Murray Rothbard and Joseph Salerno, and is designed to provide a better measure of money supply fluctuations than M2.

The Mises Institute now offers regular updates on this metric and its growth. This measure of the money supply differs from M2 in that it includes Treasury deposits at the Fed (and excludes short-time deposits and retail money funds).

In recent months, M2 growth rates have followed a similar course to TMS growth rates, although TMS has fallen faster than M2. In June 2023, the M2 growth rate was –3.5 percent. That's slightly up from May's growth rate of –3.7 percent. June 2023's growth rate was also well down from June 2022's rate of 5.6 percent.

Money supply growth can often be a helpful measure of economic activity and an indicator of coming recessions. During periods of economic boom, money supply tends to grow quickly as commercial banks make more loans. Recessions, on the other hand, tend to be preceded by slowing rates of money supply growth.

It should be noted that the money supply does not need to actually contract to signal a recession and the boom-bust cycle. As shown by Ludwig von Mises, recessions are often preceded by a mere slowing in money supply growth. But the drop into negative territory we've seen in recent months does help illustrate just how far and how rapidly money supply growth has fallen. That is generally a red flag for economic growth and employment.

The fact that the money supply is shrinking at all is so remarkable because the money supply almost never gets smaller. The money supply has now fallen by $2.8 trillion (or 15.0 percent) since the peak in April 2022. Proportionally, the drop in money supply since 2022 is the largest fall we've seen since the Depression. (Rothbard estimates that in the lead up to the Great Depression, the money supply fell by 12 percent from its peak of $73 billion in mid-1929 to $64 billion at the end of 1932.)

In spite of this recent drop in total money supply, the trend in money-supply remains well above what existed during the twenty-year period from 1989 to 2009. To return to this trend, the money supply would have to drop at least another $4 trillion or so—or 22 percent—down to a total below $15 trillion.

Since 2009, the TMS money supply is now up by nearly 184 percent. (M2 has grown by 146 percent in that period.) Out of the current money supply of $18.8 trillion, $4.5 trillion of that has been created since January 2020—or 24 percent. Since 2009, $12.2 trillion of the current money supply has been created. In other words, nearly two-thirds of the money supply have been created over the past thirteen years.

With these kinds of totals, a ten-percent drop only puts a small dent in the huge edifice of newly created money. The US economy still faces a very large monetary overhang from the past several years, and this is partly why after fourteen months of slowing money-supply growth, we are not yet seeing a sizable slowdown in the labor market.

Nonetheless, the monetary slowdown has been sufficient to considerably weaken the economy. The Philadelphia Fed's manufacturing index is in recession territory. The Empire State Manufacturing Survey is, too. The Leading Indicators index keeps looking worse. The yield curve points to recession. Individual bankruptcy filings were up 68 percent in the first half of the year. Temp jobs were down, year-over-year, which often indicates approaching recession.

Money Supply and Rising Interest Rates

An inflationary boom begins to turn to bust once new injections of money subside, and we are seeing this now. Not surprisingly, the current signs of malaise come after the Federal Reserve finally pulled its foot slightly off the money-creation accelerator after more than a decade of quantitative easing, financial repression, and a general devotion to easy money. As of July, the Fed has allowed the federal funds rate to rise to 5.50 percent, the highest since 2001. This has meant short-term interest rates overall have risen as well. In June, for example, the yield on 3-month Treasurys remains near the highest level measured in more than 20 years.

Without ongoing access to easy money at near-zero rates, however, banks are less enthusiastic about making loans, and many marginal companies will no longer be able to stave off financial trouble by refinancing or taking out new loans. For example, Yellow Corporation, a trucking company, has declared bankruptcy and will lay off 30,000 workers. Tyson Foods announced this week it is closing four chicken processing plants in an effort to cut costs. 3,000 workers are likely to lose their jobs as a result. These firms have experienced financial problems for years, but rising interest rates preclude additional delays of the inevitable. We will see more of this as more companies face the realities of higher rates. (In another sure sign of a slowing economy, state and local tax revenues have been falling.)

Meanwhile, as lenders get spooked by tightening cash availability, it's getting more difficult to qualify for a home loan, and credit availability is the tightest its been in a decade. Meanwhile, the average 30-year mortgage rate rose in July to nearly the highest point since 2002.

One of the most troubling indicators is soaring credit card debt even as interest rates soar. As of May 2023, the commercial bank interest rate rose to the highest rate measured in at least 30 years. Just last year, the interest rate hovered around 15 percent. In May 2023, it reached over 20 percent. This is happening as credit card debt and other revolving loans have reached a new all-time high.

These factors all point toward a bubble that is in the process of popping. The situation is unsustainable, yet the Fed cannot change course without reigniting a new surge in price inflation. Any surge in prices would be especially problematic given the rising cost of living. Both new and used cars are becoming increasingly unaffordable. Ordinary Americans face a similar problem with homes. According to the Atlanta Fed, the housing affordability index is now the worst it's been since 2006, in the midst of the Housing Bubble.

If the Fed reverses course now, and embraces a new flood of new money, prices will only spiral upward. It didn't have to be this way, but ordinary people are now paying the price for a decade of easy money cheered by Wall Street and the profligates in Washington. The only way to put the economy on a more stable long-term path is for the Fed to stop pumping new money into the economy. That means a falling money supply and popping economic bubbles. But it also lays the groundwork for a real economy—i.e., an economy not built on endless bubbles—built by saving and investment rather than spending made possible by artificially low interest rates and easy money.

Ryan McMaken (@ryanmcmaken) is executive editor at the Mises Institute. Send him your article submissions for the Mises Wire and Power and Market, but read article guidelines first. Ryan has a bachelor's degree in economics and a master's degree in public policy and international relations from the University of Colorado. He is the author of Breaking Away: The Case of Secession, Radical Decentralization, and Smaller Polities and Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre. He was a housing economist for the State of Colorado.

Ryan is a cohost of the Radio Rothbard podcast and the War, Economy, and State podcast, has appeared on Fox News and Fox Business, and has been featured in a number of national print publications including Politico, The Hill, Bloomberg, and The Washington Post.

mises.org

| ![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/images/live/s_gold.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/images/live/s_silv.gif)