Send this article to a friend:

May

12

2023

Send this article to a friend: May |

Why Future Returns Could Approach Zero

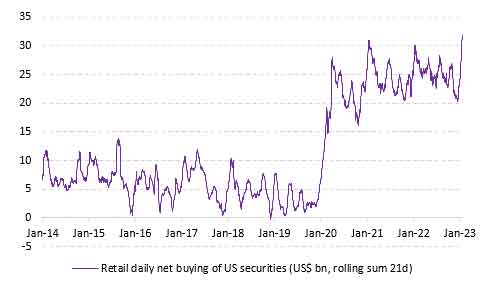

A quick search of headlines from the end of 2022 confirms that much of the retail spirit was broken. At the end of 2022, it seemed pretty clear that retail investors were done as they‘hit the bid” to liquidate stocks at a record pace. However, that was 2022. Since January, retail investors returned with a vengeance to chase stocks in 2023, pouring $1.5 billion daily into U.S. markets, the highest ever recorded.  This chase for equity risk since the beginning of the year was built on the premise of a “Fed pivot” and a “no recession” scenario. In this scenario, economic growth continues as inflation falls and the Federal Reserve returns to a rate-cutting cycle. However, as discussed in “No Landing Scenario At Odds With Fed,” that view has a fatal flaw.

In other words, if the hope of zero interest rates and a return to QE is whetting retail investor appetites, then the “no landing” scenario is problematic. Such is also why future returns may approach zero. Why Future Returns May Approach Zero The speculation of outsized returns by retail investors is unsurprising, given that most have never seen an actual bear market. Many retail investors today didn’t make their first investments until after the financial crisis and, since then, have only seen liquidity-fueled markets supported by zero interest rates. As discussed in “Long-Term Returns Are Unsustainable.”

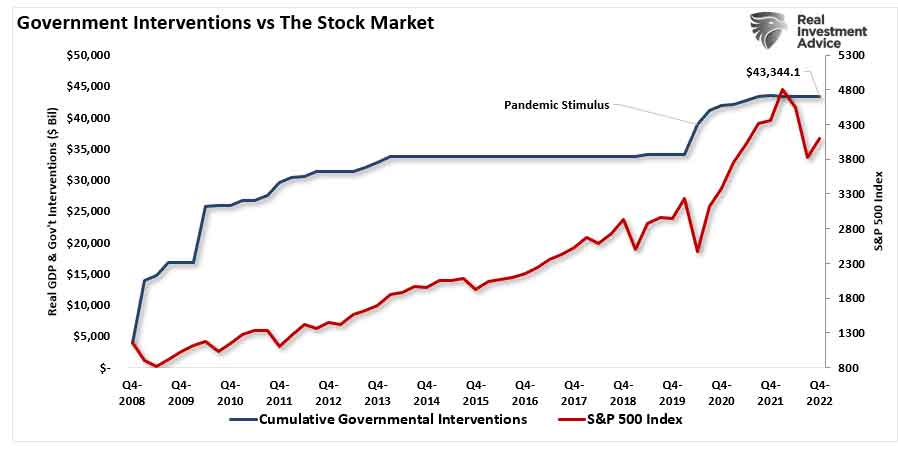

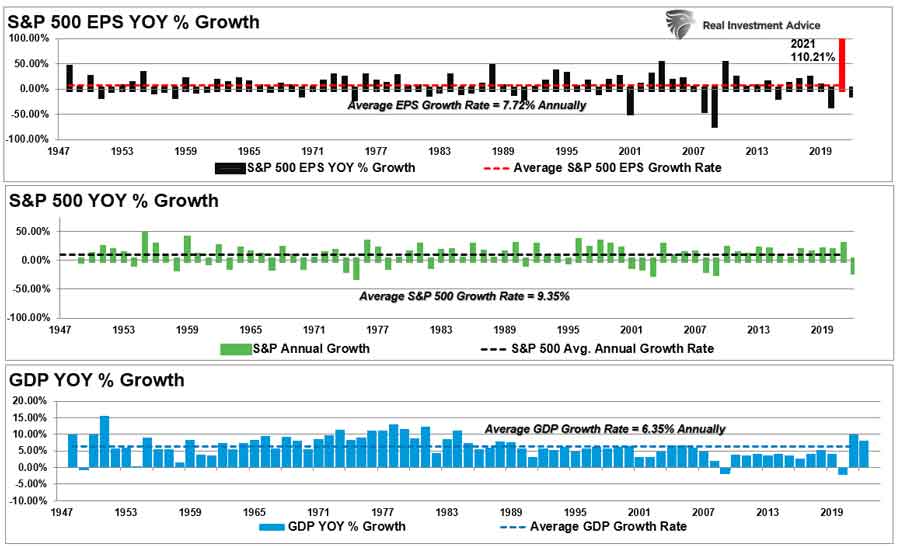

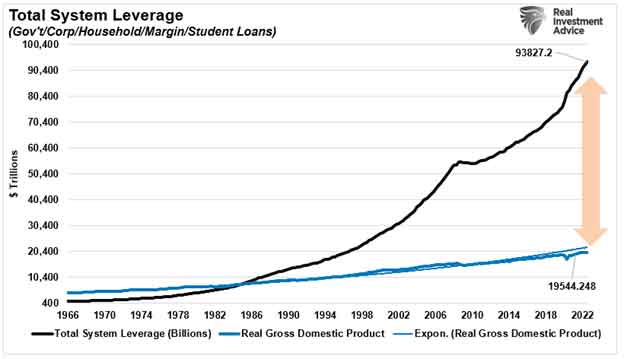

Of course, those excess returns were driven by the massive floods of liquidity from the Government and the Federal Reserve, including trillions in corporate share buybacks and zero interest rates. Since 2009, there has been more than $43 Trillion in various liquidity supports. To put that into perspective, the inputs exceed underlying economic growth by more than 10-fold.  However, after a decade, many investors became complacent in expecting elevated rates of return from the financial markets. In other words, the abnormally high returns created by massive doses of liquidity became seemingly ordinary. As such, it is unsurprising that investors developed many rationalizations to justify overpaying for assets. Commitment To Growth The problem is that replicating those returns becomes highly improbable unless the Federal Reserve and Government commit to ongoing fiscal and monetary interventions. The chart below of annualized growth of stocks, GDP, and earnings show the outsized anomaly of 2021.

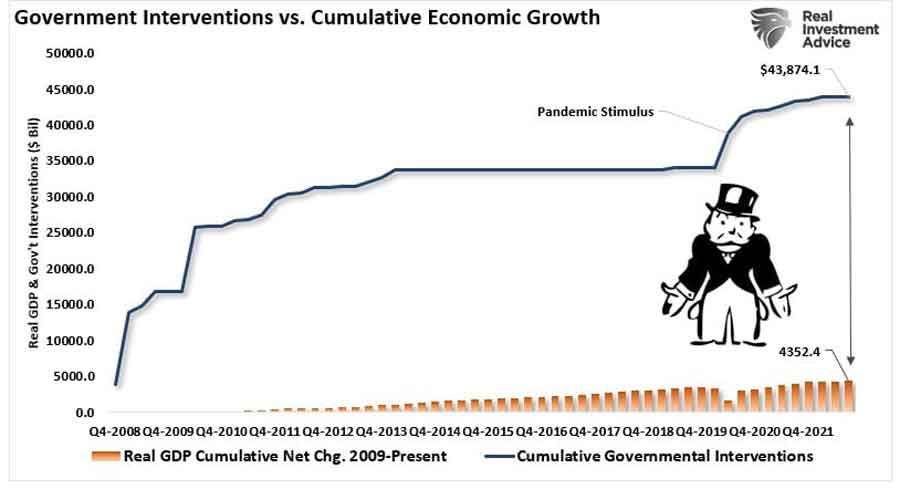

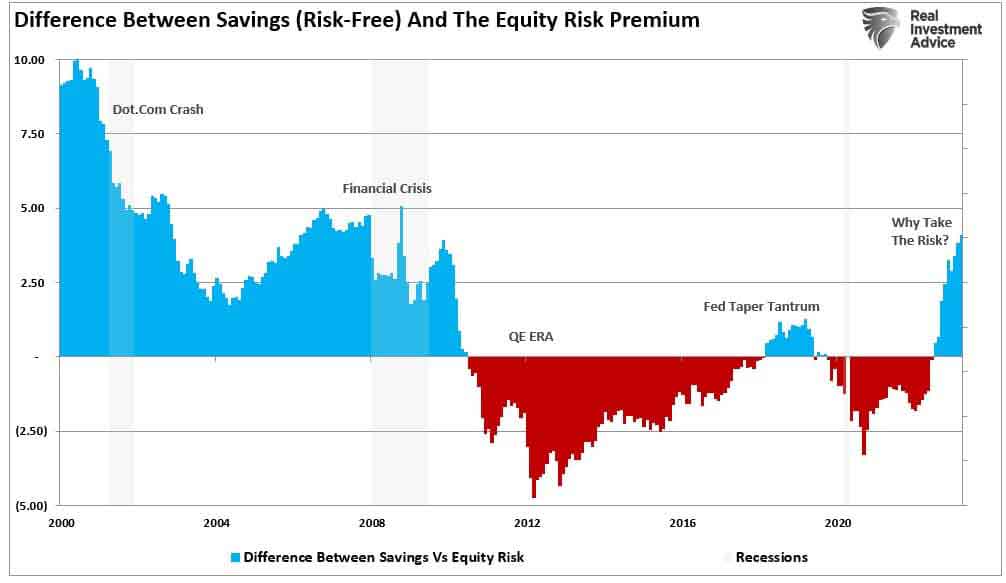

Since 1947, earnings per share have grown at 7.72%, while the economy has expanded by 6.35% annually. That close relationship in growth rates is logical, given the significant role that consumer spending has in the GDP equation. The market disconnect from underlying economic activity over the last decade was due almost solely to successive monetary interventions leading investors to believe “this time is different.” The chart below shows the cumulative total of those interventions that provided the illusion of organic economic growth.  Over the next decade, the ability to replicate $10 of interventions for each $1 of economic seems much less probable. Of course, one must also consider the drag on future returns from the excessive debt accumulated since the financial crisis.  That debt’s sustainability depends on low-interest rates, which can only exist in a low-growth, low-inflation environment. Low inflation and a slow-growth economy do not support excess return rates. It is hard to fathom how forward return rates will not be disappointing compared to the last decade. However, those excess returns were the result of a monetary illusion. The consequence of dispelling that illusion will be challenging for investors. Will this mean investors make NO money over the decade? No. It means that returns will likely be substantially lower than investors have witnessed over the last decade. But then again, getting average returns may be “feel” very disappointing to many. At 4%, Cash Is King Another problem weighing against potential future returns is the return on holding cash. For the first time since 2009, the alternative to taking risks in the stock market is just “saving money.” Obviously, “safety” comes at the cost of the return, but at 4% or more, savers now have an alternative to investing. However, this works against the Fed’s goal of increasing the wealth effect in the financial markets. Following the financial crisis, Ben Bernanke dropped the Fed funds rate to zero and flooded the system with liquidity through “quantitative easing.” As he noted in 2010, those actions would boost asset prices, lifting consumer confidence and creating economic growth. By dropping rates to zero, “risk-free” rates also dropped toward zero, leaving investors little choice to obtain a return on their cash. Today, that narrative has changed with current “risk-free” yields above 4%. In other words, it is possible to “save” your way to retirement. The chart below shows the savings rate on short-term deposits versus the equity-risk premium of the market.

One of the problems with the “cash hoard” in 2023 is there is no incentive to reverse savings into “risk assets” unless the Fed drops rates and reintroduces “quantitative easing.” However, as discussed in “Banking Crisis Is How It Starts,” if the Fed reverses to accommodative policies, it is because “something broke.” Such won’t be the time to take on more risk, but less. When you start considering the implications of a market plagued by high valuations, slow growth, and the potential for less liquidity, it is easy to make a case for lower future returns. While that does not mean returns will be zero every year, at the end of the decade, we may look back and ask what was the point of “investing” to begin with.

|

Send this article to a friend:

|

|

|