Send this article to a friend:

April

06

2023

Send this article to a friend: April |

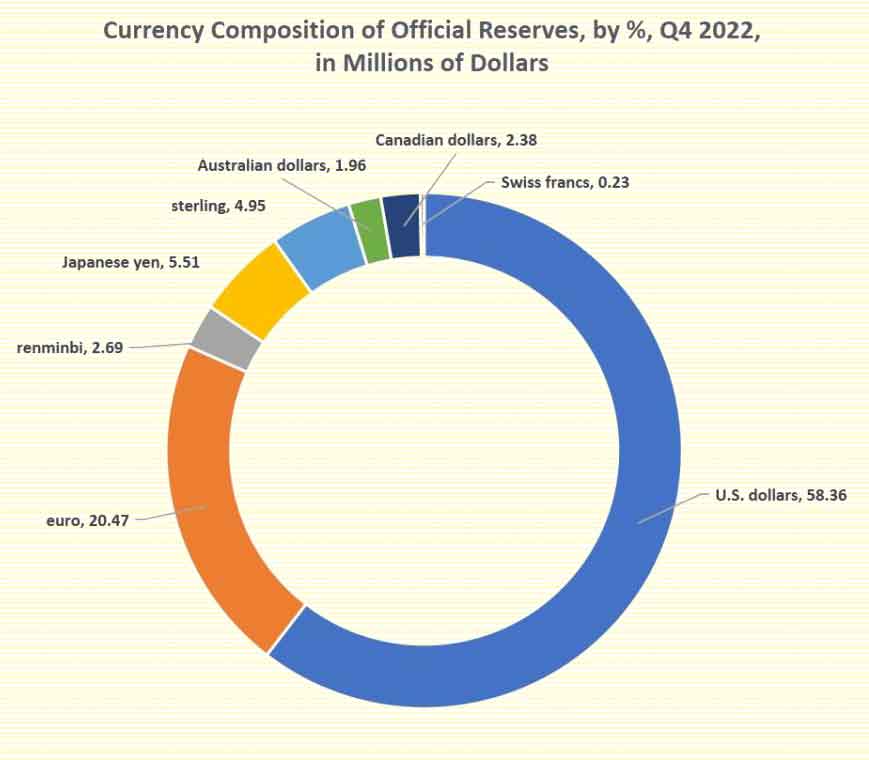

Why the Regime Needs the Dollar to Be the Global Reserve Currency

Much of the analysis was framed to stoke the public’s fears of Chinese geopolitical power, and the Fox segment was especially hyperbolic in its predictions of near-total economic devastation resulting from any movement away from the dollar in international trade and reserves. Yet both segments are correct that events are piling up that point to at least a gradual decline in the dollar’s preeminence in the global economy and that this could lead to serious economic trouble for Washington. Events are not moving as quickly as the pundits are predicting, but they are moving, and if current trends continue, the United States will find itself facing a new and enduring era of stubborn price inflation and weakening US geopolitical power. The Beginning of a Trend? Much of the discussion around the decline of the dollar is framed as a matter of the Chinese renminbi (RMB, or yuan) becoming the global reserve currency. This purported imminent replacement of the dollar with the RMB, however, is not going to happen any time soon. There are many reasons for this. China still uses capital controls, its economy is not nearly as open as the US economy, and US government debt still looks less risky than Chinese debt. Yet we are witnessing a growing trend in the world’s regimes of moving away from the dollar as the overwhelming favorite among currencies used for international trade. First, there is the recent agreement at the Russia-China summit to carry out trade transactions “between Russia and the countries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America,” as Vladimir Putin put it. This would be quite a change from the status quo in which nondollar transactions make up a tiny portion of international trade settlements. This trend is catching on elsewhere as well. Last month, China and Brazil reportedly “struck a deal to allow companies to settle their trade transactions in the two countries’ own currencies, ditching the United States dollar as an intermediary.” Meanwhile, a French company bought sixty-five thousand tons of liquified natural gas (LNG), meaning “Chinese national oil company CNOOC and France’s TotalEnergies have completed China’s first yuan-settled LNG trade.” Oil giant Saudi Arabia has also repeatedly stated that it’s amenable to opening up its oil trade to currencies other than the US dollar, with an eye toward accepting RMB. None of this threatens to immediately send the dollar into a tailspin or “collapse.” The dollar’s role in the world economy is still huge, and the dollar remains the most used currency by far. This becomes all the more obvious when we look at how much the US dollar still dominates foreign exchange reserves—which are assets in foreign currencies held on reserve by central banks. These reserves are partly an indication of just how much central banks anticipate dollars will be needed to engage in international trade. Dollars still make up 58 percent of foreign exchange reserves. That’s far above even the second-place currency, the euro, which is at a mere 20 percent. All other currencies are far behind that. The Japanese yen makes up about 5.5 percent of all reserves, and the pound sterling makes up under 5 percent. The RMB is in fifth place at about 2.7 percent.  Source: International Monetary Fund. While the RMB is not about to replace the dollar, general movement away from the dollar—in favor of a mixture of other currencies—is indeed in place. In fact, as of the fourth quarter of last year, the dollar made up the lowest percentage of foreign reserves since 1995, falling from 66 percent of reserves in 2014. Why Does Reserve Currency Status Matter? Being the country whose currency enjoys global reserve status brings both domestic and international advantages to the US regime. Domestically, reserve currency status brings a greater global demand for dollars. This means more of a global willingness to absorb dollars into foreign central banks and foreign bank accounts even as the dollar inflates and loses purchasing power. Ultimately, this means the US regime can get away with more monetary inflation, more financial repression, and more debt before domestic price inflation gets out of hand. After all, even if the US central bank (the Federal Reserve) creates $8 trillion in new dollars in order to prop up US asset prices, much of the world will take those dollars out of US domestic markets, and this will reduce price inflation in the US—at least in the short term. Moreover, the fact the dollar dominates in global trade transactions means more global demand for US debt. Or, as Reuters put it in 2019, the dollar is used “for at least half of international trade invoices—five times more than the United States’ share of world goods imports—fuelling demand for U.S. assets.” Those assets include US government debt, and this pushes down the interest rate at which the US government must pay on its enormous $30 trillion debt. This also decreases the likelihood of a US sovereign debt crisis. Domestically in the US, reserve status for the dollar mutes inflation, lowers interest rates, and enables more government spending. Internationally, the US government enjoys many benefits from reserve status. For example, the US regime is much more easily able to impose economic sanctions on rival states, thanks to the role of dollars in international trade and banking. Dollars are central to the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) system, which is the main messaging network through which international trade transactions are initiated. In recent years, this control of SWIFT has enabled the US to largely exclude both Iran and Russia from much of the international banking system. The US has also frequently threatened sanctions on a number of countries that have not been quick to accept US primacy in all regions of the world. This power is further enhanced due to a longstanding agreement in which oil-producing Arab states—primarily Saudi Arabia—use dollars for oil transactions in exchange for certain US military commitments. These so-called petrodollars further secure US dominance in the geopolitical realm. [Read More: “Why the End of the Petrodollar Spells Trouble for the US Regime” by Ryan McMaken] Weakening Reserve Status Means a Weakening US Regime Often, discussion about the dollar’s reserve status creates a false dichotomy between total domination of the global monetary system on one hand and complete abandonment of the dollar on the other. A more likely scenario is that the dollar will weaken considerably but will remain among the most often used currencies. After all, even after the pound sterling lost its status as reserve currency in the 1930s, it did not disappear. For example, let’s say the US dollar sinks to 40 percent of all foreign reserves and is only used in one-third of all international trade invoices—instead of one-half, as is now the case. This would not necessarily destroy the dollar or the US economy, but it would certainly weaken the US regime’s geopolitical position. As global infrastructure around other currencies grows, it will become easier for regimes and private firms to circumvent US sanctions. Perhaps more importantly, a world less awash in dollars will mean a world with less demand for US assets such as US government debt. That means higher interest rates for the US government and less of an ability to finance elective wars by inflating the currency. In other words, even a weakening of the dollar’s global demand will limit the US regime’s ability to throw its weight around internationally. This is why in a recent interview with Fox News, US senator Marco Rubio worriedthat if other countries are using their own currencies in trade, “we won’t be talking about sanctions in 5 years . . . because we won’t have the ability to sanction them.” This doesn’t require the full collapse of the dollar. It just requires a framework for other currencies. It will take a while, and some attempts will fail. But those frameworks are being built now, and not all of them will fail. How to Stop the Slide Away from the Reserve Currency For obvious reasons, then, the US regime wants to maintain the US dollar’s status. If the US regime were motivated to ensure economic prosperity and security for Americans, it could easily do so. All that is required is to end the US central bank’s easy-money policies, reduce monetary inflation, and rein in deficit spending. This would immediately buttress both the real and perceived value of the dollar and make the dollar far more attractive as a currency that holds its value. Moreover, the US regime could ensure continued widespread use of the dollar if it stops using the dollar to bully other regimes and wage economic war on every regime that annoys the foreign-policy establishment. Without the dollar’s weaponization—especially with reduced monetary inflation—there is very little motivation to abandon the dollar in favor of other currencies. After all, most other regimes inflate their own currencies at least as much as the dollar and engage in widespread deficit spending. Economically, the dollar remains less turbulent than both the euro and yen. So long as Washington does continue to weaponize the dollar, however, other regimes will have good reason to escape the dollar system. It’s difficult to see how the US regime will abandon this status quo any time soon, however. Washington is addicted to deficit spending, monetary inflation, and international meddling in the name of US primacy and war. It won’t stop until domestic inflation becomes politically unbearable and foreign states finish building off-ramps from the dollar system.

mises.org

|

Send this article to a friend:

|

|

|