Send this article to a friend:

February

28

2024

Send this article to a friend: February |

Don’t Be Surprised If The Fed Raises Interest Rates

I’ve been right in my prediction that we will get a soft landing with no recession, with the important proviso that the Fed pauses its rate-hiking cycle, which it has already done. Remarkably, the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates high enough to reverse the inflation rate, at one point at a 40-year high, without causing a severe downturn. And it’s done it in an extremely short amount of time. The Federal Open Market Committee meets seven more times, meaning seven more opportunities to raise, lower, or pause interest rates, with the next meeting happening on March 19-20. Until now, I’ve gone along with market expectations for three quarter-point rate cuts starting in 2024, with the first one likely in May or June. (The Fed said after its December meeting it was looking at three reductions in 2024.) However, I’m beginning to change my mind about rate cuts happening mid-year, and maybe not at all in 2024. In fact, the Fed could very well start raising rates again, due primarily to a healthy economy, including a strong dollar and job market, and persistently high inflation. Persistent inflation On Friday, Jan. 26, the release of the PCE price index strengthened the argument that the Fed will reduce rates later this year. Core PCE (i.e., stripping out food and energy) is the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge. On a six-month annualized basis, core PCE was below the Fed’s 2% target in December for a second straight month, at 1.9%. On an annualized basis core PCE was 2.9%. Even if we take the latter figure, inflation appears to be coming down to the Fed’s 2% target. When the Federal Open Market Committee had its regular meeting Jan. 30-31, it voted for the fourth consecutive meeting to leave interest rates alone, at 5.25-5.5%. But hold on. The Fed also made clear it is not ready to start cutting, and particularly will not lower rates in March, as previously expected. In mid-January, Forbes predicted the Fed will start cutting interest rates around mid-year, “but the cuts will be slow and gradual.” It noted the risk of recession has fallen according to the economists, and that the continual increase in employment reinforce that view. But then this: while the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose just 3.4% from a peak of 9.1% in mid-2022, core PCE grew by 3.2% in the most recent 12 months — down from a peak of 6.5%, but 1.2% higher than the Fed’s 2% target. Forbes commented, “the employment data tell them there’s no urgency” to cut rates, and that “Most if not all Fed policy makers believe that allowing inflation to continue above the target would lead to behavioral changes by consumers, businesses and investors, and then a severe recession would be needed to bring inflation down.” Fast forward a month. A new inflation report, released Feb. 13, showed January inflation running hotter than expected. Consumer prices rose 3.1% from a year earlier, worse than the forecasted 2.9%. Core CPI, which excludes food and energy, climbed 0.4% in January, up from 0.3% in December and 3.9%, year on year. Among the categories where inflation remains relatively high, according to the Labor Departments, are car insurance, up 20.6% in the past year, personal care (5.3%) and medical care (1.1%). While overall grocery inflation declined to 1.2%, compared to January 2023, some categories remain elevated. These include juices and drinks (29%), sugar (7.2%) and beefsteaks (10.7%). For economists, the data showed inflation remains sticky, and gave them a partial answer as to when the Fed will make the first rate cut: “expect to wait longer”. This was reinforced by Fed Chairman Jay Powell, who told ’60 Minutes’ that the central bank wants to see more proof that inflation is cooling before cutting rates. CBS News quoted one economist saying that a lower inflation rate doesn’t mean that prices of most things are falling; rather, it means prices are rising more slowly. Food prices, for instance, are 25% higher than in January 2020, while rents are up 22% over the same period. Many economists delayed their rate cut projections following the January inflation report to June 11-12 at the earliest, definitely not March 19-20, and probably not April 30-May 1. Bloomberg was more hawkish on the prospects of a rate cut, pointing out that core PCE in January rose 0.4% from December, marking the second straight monthly acceleration in a gauge that has largely been receding over the past two years: Underlying US inflation probably rose in January by the most in a year, as tracked by the Federal Reserve’s preferred metric, highlighting the long and bumpy path to taming price pressures. When the next PCE data point is released this Thursday, Feb. 29, Bloomberg Economics says, “The stage is set for monthly PCE inflation to jump following hot CPI and PPI [Producer Price Index] reports.”

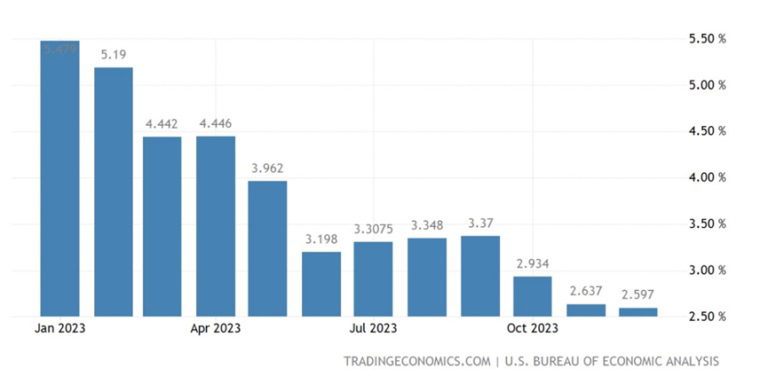

PCE price index, annual change. Source: Trading Economics Yet another contrarian opinion is that of Jim Grant, founder of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer. Speaking on CNBC’s ‘Power Lunch’ last week, Grant said what surprises him is the unanimity of the position that we are in for a series of interest rate reductions this year. He notes the president of the Dallas Fed, Lorie Logan, said in a speech in early January that the Federal Reserve shouldn’t rule a rate raise out. His own reasons for continued Fed tightening include the fact that the government is running a budget deficit of 5-6% in 2024, the unemployment is a low 3.7%, the stock market is making new highs, and credit spreads are compressed. “The world expects everything except what I deem to be a not improbable thing, which is to say inflation might surprise to the upside. It might persist in surprising and in those circumstances the Fed might very well have to raise rates,” Grant said. Strong dollarAlong with inflation data, I’m closely watching the US dollar as an indication of what the Fed might do. A high dollar is a reflection of a strong economy; why would the Fed cut interest rates if the economy is purring along nicely? Rallying stock markets are attracting money into the greenback, along with reasonably high bond yields. Bloomberg notes the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index has been gaining strength and appears to be consolidating at levels comfortably higher than pre-covid. The US Dollar Index (DXY) nearly slipped below 100 at the end of the year but has been steadily climbing, as the chart below shows.

Source: MarketWatch Same for the 10-year Treasury bond, although it fell briefly under 4% following weak job figures and concerns about the regional banking sector on Feb. 1.

Source: MarketWatch Jefferies LLC’s Brad Bechtel says the shift in expectations towards cutting rates later and by less is boosting the outlook for the dollar, despite the fact that the market currently only sees a cut. For more reasons the dollar has done so well, consider the fact that we are in an election year, and good polling numbers for Trump are converting into a strong dollar. (Trump’s trade war with China, you may recall, was good for the buck. A possible post-election trade war would prompt the selling of other currencies.) Bloomberg takes a longer view, noting that the United States already has an “America First” economy, as the world shifts from globalization to a system of trading blocks and more localized economies. Barclays Bank’s Themos Fiotakis argues: Over the past 20 years, the US has had higher productivity growth, improvement in its terms of trade, and higher returns on capital. It has outperformed other major economies in those areas because the US has chosen a different business model. By that, Fiotakis means the country has opted for policies that have supported its domestic economy, while others stuck with globalization. Bloomberg explains: Since the 2008 crisis, and the brief commodities boom that followed, globalization has stalled and even reversed. Growth has been slowing. Europe, China, and many emerging markets are exposed to this, while the US has at least to an extent decoupled. Policies that worked included backing energy independence, which established the US as a net energy exporter, reducing risk of supply or price shocks. Washington’s policies have also worked in Big Tech’s favor, fostering giants that have been very dominant, and attracted overseas funds. Conclusion Given the new information that has been presented, it’s not so surprising to read that Bloomberg’s World Interest Rates Probability function, derived from fed funds futures prices, shows the odds for a rate cut by June have been almost eliminated. On Thursday the PCE data for January is coming out, and staff at Bloomberg Economics show, “it’s expected to take an active step up.” Anyone can speculate as to how the Fed will respond to the new inflation data, but the important thing is how the data conforms, or doesn’t conform, to the Fed’s expectations. The First Quarter 2024 Survey of Professional Forecasters predicts higher output growth and a brighter labor market in 2024, both of which would signal the economy can handle continued tightening. The 34 forecasters surveyed by the Bank of Philadelphia think the economy will grow (annually) by 2.1% this quarter, and that the GDP will increase 2.4% for the year, up 0.7% compared to a previous survey. They expect the unemployment rate to average just 3.9% in 2024, with job gains in the current quarter at a rate of 235,800 per month. Q1 headline CPI inflation will average 2.5%, down from the previous survey’s 2.8% prediction, with headline PCE estimated at 1.9%, below the earlier estimate of 2.5%. The forecasters predict lower core PCE inflation but higher core CPI inflation over the current quarter. On an annual basis, they project both headline and core PCE inflation will be 2.1%, down from the previous predictions of 2.4%. These are ambitious targets. What if they turn out to be wrong, and inflation is higher than forecasted? The Fed will then have two choices: hold the line and wait to see if next month’s data improves; or risk throwing the markets into a tizzy by raising the federal funds rate. On the other hand, if inflation comes in close to expectations, or better, that would strengthen the argument for a cut. But the Fed doesn’t want to slash rates too quickly and then have to reverse course, say if inflation were to suddenly skyrocket. Another wildcard to throw into the question of if and when the Fed cut rates, is the $13 trillion of government debt about to roll over at higher levels of interest. If the Fed cuts rates, it would act as a powerful disincentive to bond investors, who the federal government relies upon to shoulder its considerable debt burden. If buyers for US Treasuries dry up, the Federal Reserve will have to step in as the buyer of last resort. Printing money and buying bonds, aka quantitative easing, is highly inflationary, and the last thing the Fed wants to do. We conclude that the most likely course of action right now is for the Fed to either maintain current interest rates or raise them again if inflation data comes in hotter, as it is expected to. Covid-related supply chain issues have more or less been fixed, and that has helped cool prices, but now there are problems getting food, energy and other goods through the Panama Canal and the Suez Canal. The only reason for a rate cut is political, i.e., to help get the Democrats re-elected. Other than that, I don’t see any reason for one, because inflation is not yet tamed.

|

Send this article to a friend:

|

|

|